What do aquatic plants need?

Similar to terrestrial plants, aquatic plants require a supply of nutrients to grow well. This has been well studied in terrestrial science, and the chemical elements necessary for growth can be grouped into two major groups:

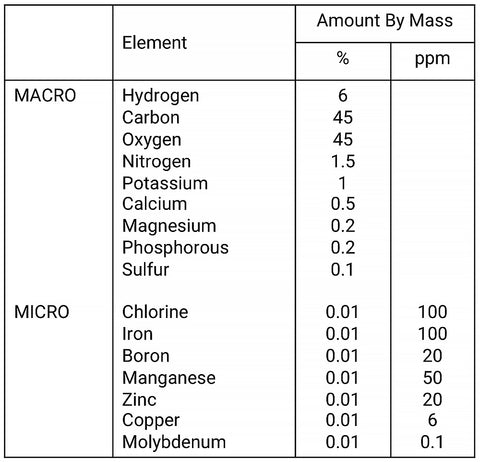

Macro nutrients |

Micro Nutrients |

| Used in large quantities by plants: Nitrogen, Phosphorous, Potassium, Calcium & Magnesium, Sulfur | Used in very small quantities by plants: Iron, Chlorine, Boron, Manganese, Zinc, Copper and Molybdenum. |

Macro-nutrients, together with carbon makes up ~96% of plant mass. Hence, the term macro-nutrients. A lot of the basic building blocks for plants come from air/water; hydrogen, oxygen. The rest of the elements come from soil (for terrestrial plants that’s where nutrients accumulate) and water (aquatic plants can take in nutrients through the water column).

Note that Carbon makes up 45% of dry mass, but ‘naturally’ dissolved carbon in tap water is usually low. Compared to carbon, other macro nutrients make up only a small percentage of dry mass! Plants use 10 times more carbon by mass than all the other macro-nutrients combined. This is why CO2 injection is such a big impact factor in plant growth outcomes. Tank CO2 levels without CO2 injection hover around 2-3ppm as it reaches equilibrium levels with atmosphere given gas pressure laws concerning liquids. Natural waters supportive of plant growth have levels closer to 10-30ppm. With CO2 injection we can push these levels even higher, close to 40+ppm. Consequently, growth rates in an injected tank are 5-10 times that compared to a non CO2-injected tank. The nutrient requirements of a CO2 injected tank also scales up in a similar fashion.

Micro-nutrients are used in very very small amounts. It is sometimes hard to imagine the difference in magnitude in these micro-amounts. Plants use 100X more potassium than Iron, for example.

A typical plant dry mass composition is shown in the table below:

Liebig’s law of the minimum is the principle that growth is controlled by the scarcest resource, meaning that providing an excess of other nutrients will not stimulate growth, if another critical variable is not proportionately increased. This is why a comprehensive fertiliser is so important.

Notable elements and common forms:

Nitrogen (Ammonia NH3, Nitrates NO3): Element that plants use the most aside from Carbon. Major growth regulator – nature is frequently nitrogen limited, and plants are quick to snatch up new sources of nitrogen. By altering N levels in the tank we can accelerate or slow down growth rates. Some species of aquatic plants get redder coloration when N levels are low due to delayed development of chlorophyll (Rotala rotundifolia & variants, Ludwigia arcuata/brevipes, Limnophila aromatica). Generally, N dosing in a tank should be kept stable to prevent plants from constantly re-programming their growth rates which leads to many problems. Livestock waste contributes a significant amount of N if tank is well stocked.

Phosphorus (Phosphates, PO4): Colored plants become more pale when PO4 is lacking. Tanks with significant amount of livestock generally have quite a bit of PO4.

Potassium (K): Potassium is utilized in many essential plant functions. For regions where tap water does not contain potassium, planted tanks quickly run into multiple problems when K levels are insufficient. This is readily provided in most commercial fertilizers (though not necessarily at optimal amounts). This is not provided optimally through livestock waste.

Iron (Iron chelates, soils, Fe): Iron is an immobile nutrient (unlike NPK above) and plants cannot transfer Fe from old leaves to feed new growth. Thus a lack of Fe is first seen as the yellowing of new leaves and poor pigmentation in colored plants. Unlike what most hobbyists think; providing excess iron does not stimulate additional pigmentation in red plants. Regular dosing to keep it at a sufficient level is more important.

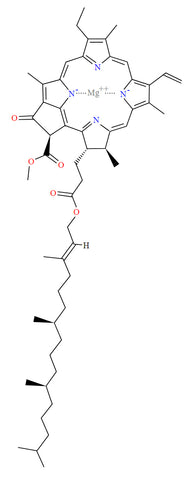

Magnesium (Mg): Key molecule in chlorophyll. (above) Available quite commonly in tap water, but for regions where tap water has no Mg, dosing it regularly is critical. Many commercial fertilizer miss this in their formulation.

Trace elements (Boron B, Copper Cu, Boron B..etc): Plants use only tiny amounts of these, but they do affect both plant coloration and growth form. In high speed growth rates of CO2 injected tanks, it is easy to get sub-optimal levels of trace elements. Required dosage is tiny, but should be done regularly.

How much to dose of each element is covered in the dosing guide here.

Nutrients from livestock waste? – It just ain’t enough

The planted tank is an enclosed environment. Unlike a truly natural environment, there is no inherent cycle of nutrient replenishment, where organic decomposition and mineral erosion return nutrients back to the soil. Aquarium soil substrates in a planted tank can provide nutrients for a good amount of time, but all substrates eventually deplete. Nutrients that are soluble get removed with water changes; and depending on what is in one’s tap water- may or may not get replenished.

Depending on fish waste looks good in theory, but is often incomplete. No fish we know of produces, for example, chelated iron as waste.

In many planted aquariums, elements such as potassium and Iron are usually lacking unless we dose them. Some tanks seek to depend on livestock waste as fertilizer. Organic waste also doesn’t directly decompose cleanly – there are many by products in the process, and having elevated levels of organic waste in the tank is a good trigger for algae blooms. Livestock waste from fish heavy tanks can produce significant amounts of Nitrates and Phosphates. However, other elements such as iron, trace elements, potassium will most likely to at sub-optimal levels. While some tanks do survive with the “no dosing” approach – they are never the ones that get the best growth.

The 2Hr approach is always to strive for the more optimal scenario, rather than take chances with the bare minimum, hence we would highly recommend complete fertilizers that cover all angles nutrient-wise.

When aquatic plants get all access to all their nutrient needs – they can be grown more densely and exhibit better coloration. You won’t see examples such as these in “no dosing” tanks. Even the humble Bucephalandra; one of the easiest aquatic plants to grow, show their full potential only when their needs are met comprehensively. Whether you are running CO2 or not, dosing makes a significant difference to plant health.

What happens when there is a lack of nutrients?

Generally, when plants do not receive the nutrients they require, the first thing that happens is that growth slows. For rooted species, energy will be channeled to root growth in search of nutrients in the substrate layer. Then, depending on what kind of nutrient is lacking, a mix of symptoms can occur – in some cases, leaves become paler in color or new shoots become whitish. Stems appear thin and leaves may be smaller than usual. When mobile nutrients such as NPK & Mg run too low, plants can scavenge minerals from their old leaves and channel it to new growth. This leads to premature shedding or yellowing of older leaves.

Weak and unhealthy plants are the number 1 cause of algae. Thus feeding plants regularly to ensure their good health is critical to deter algae.

Deficiency charts are not accurate and hobbyists without experience should be careful about drawing quick conclusions that any and all plant health issues are nutrient related. (More likely is the case that issues arise from non-nutrient related factors)

We do not think that dosing only when deficiencies occur is a good method, as the plant will already be stunted and problems like algae would already have spawned. Rather than wait for deficiencies to manifest, an easy way to avoid deficiencies in general is to have a regular dosing regime of all required elements. This is easily achieved with wide spectrum liquid fertilizer. This is the default approach of most successful planted tanks.

Anubias barteri nana showing long term magnesium deficiency.

Head to this section to learn more about fertilization.